The 500th anniversary of the Reformation in 2017 was a momentous milestone that commemorated Martin Luther sparking the Reformation through the posting of the 95 Theses on the castle church door on October 31, 1517, in Wittenberg, Germany. The impact of that event and its consequences were certainly not known at that time, but unfolded through the Reformation movement in the following years. We are following those events 500 years later and reflecting on the consequences and blessings.

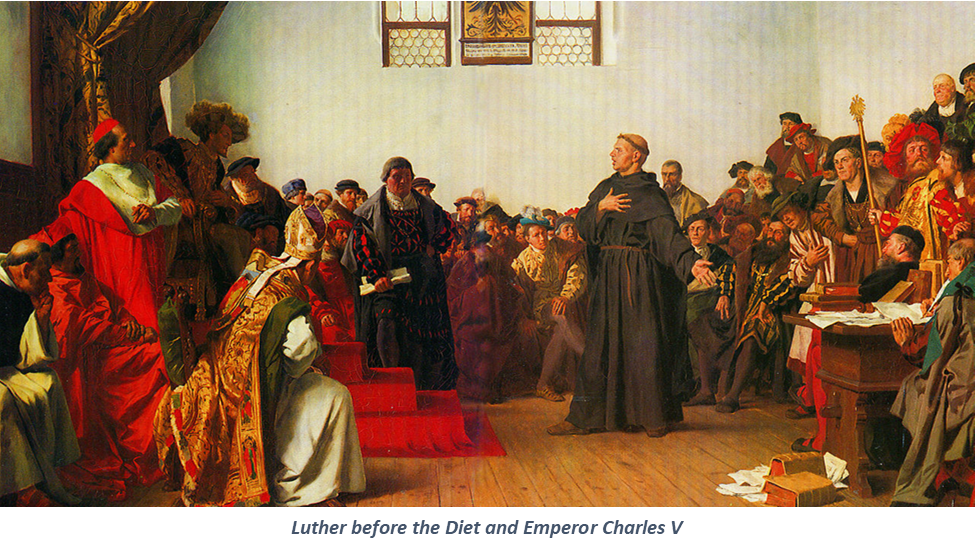

Perhaps one of the most significant moments of the Reformation, and certain in Luther’s life, was his appearing before the Congress of the Holy Roman Empire, before counts and nobles, princes and electors, and the Holy Roman Emperor himself, the young Charles V. What Luther said at this moment would set the Reformation on an irreversible course against the forces of the pope and emperor. This was the moment of decision where Luther’s faith in God and his conviction that the Scriptures were the highest authority in the church would lay the foundation for the Reformation movement.

The imperial congress, called a Diet, was held in the city of Worms (pronounced “Vohrms”), one of most ancient cities in Germany. This is where we get the name of this event, called the Diet of Worms. It was a four month long gathering of the top levels of government in the Holy Roman Empire – nobles, knights, counts, and free cities called “The Estates” and the top rulers called “The Electors,” which included three archbishops and also the Prince Elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise, who was Luther’s protector.

The imperial congress, called a Diet, was held in the city of Worms (pronounced “Vohrms”), one of most ancient cities in Germany. This is where we get the name of this event, called the Diet of Worms. It was a four month long gathering of the top levels of government in the Holy Roman Empire – nobles, knights, counts, and free cities called “The Estates” and the top rulers called “The Electors,” which included three archbishops and also the Prince Elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise, who was Luther’s protector.

The Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, was from the Spanish line of the Hapsburg family, and was only 21 at the time. In fact, this was his first imperial diet, and all eyes were on the young emperor as he had to grapple with internal and external threats from France, from the pope, from the Muslim armies advancing into Europe, and now a theological dispute with a little German monk that threatened the unity that his empire needed precisely at this moment.

After Luther started the debate about indulgences in 1517, the discussions focused on the nature of the Gospel (saved by grace through faith alone – not by works) and the authority of the Scriptures (which Luther claimed were infallible, unlike popes and councils, which could err). As Luther promoted his ideas at the Heidelberg Disputation in 1518 and the Leipzig Debate with John Eck in 1519, his attacks against the church hierarchy over the abuses they tolerated and the false doctrine they promoted reached the ears of the archbishops and the pope himself. Luther’s key writings in 1520 (On the Freedom of a Christian, the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, and Address to the Nobility of the German Nation) caused so much public antagonism to Rome that some feared a mass uprising. These writings were the last straw. Several church leaders in Germany made it their goal to squash the debates caused by Luther and reinforce the authority of the church. They succeeded in having Luther excommunicated by the pope in January, 1521. They pressed the emperor to ratify the pope’s decree with a civil injunction against Luther, showing the unity of church and state against heretics. This was to be taken up by the Diet in Worms.

In a strange twist of events, including a delicate dance of politics, piety, and diplomacy, the influence of Fredrick the Wise and Luther’s supporters managed to somehow change the course of the proceedings, so that rather than simply condemn Luther, he should be brought forward to give an opportunity to speak. Some thought this was playing with fire, as it might give the heretic an opportunity to further spread his teachings and foment the disgruntled public against Rome. Eventually, the emperor agreed to have Luther summoned to Worms, and sent his herald to personally fetch Luther from Wittenberg, about 325 miles away.

The herald reach Wittenberg on March 29, and on April 2, Luther set out in a covered wagon with his companions. Their journey to Worms in some ways felt like a death march, where Luther was following in the footsteps of other reformers like John Hus and John Wycliffe, who were condemned and burned. Would Luther go to the flames? He wrote to his friends that he was prepared to give his life for his faith and the cause of Christ. On the other hand, the journey was like a victory parade for a celebrity, and a march of triumph where Luther was greeted by throngs of people who had read his writings and felt like he was some sort of savior to the German people. He was resisting the vile Roman abuses in Germany and protecting the hearts and livelihood of the people. Luther was portrayed as a German Hercules, and pictures and prints appeared that represented violent aggression against the Roman church leaders. Some were moved by faith and piety, some were moved by patriotism and populism. Luther knew where his heart and faith were grounded – in God’s Word and the sake of the Gospel, and he felt that in some ways his journey to Worms was like Christ’s procession into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, with cheering crowds and a cross before him.

After journeying through towns and cities such as Leipzig, Weimar, Erfurt, Eisenach, and Frankfurt, Luther and his entourage entered Worms on April 16 to the sound of trumpets and crowds of several thousand. The pressure was on the Diet to deal with the Luther matter delicately. The dignitaries in Worms lined up to meet personally with Luther and give him encouragement.

The next day, April 17, Luther was brought into the hall before the assembled diet. He had to be escorted through back doors and passageways because of the crowds outside. As a monk, Luther had not been exposed to such worldly pomp and circumstance. He looked all around the hall and even smiled and waved at people he recognized, and was consequently scolded by the imperial marshal. Luther was not accustomed to the ways of the courts and nobility. As soon as Charles saw Luther, he said “He will not make a heretic out of me.”

The next day, April 17, Luther was brought into the hall before the assembled diet. He had to be escorted through back doors and passageways because of the crowds outside. As a monk, Luther had not been exposed to such worldly pomp and circumstance. He looked all around the hall and even smiled and waved at people he recognized, and was consequently scolded by the imperial marshal. Luther was not accustomed to the ways of the courts and nobility. As soon as Charles saw Luther, he said “He will not make a heretic out of me.”

Luther’s books were in a pile in the middle of the room, and Luther was asked if he would recant what he had written. He replied that the writings were indeed his own, but since they contained matters of faith and the Word of God, he asked to respond the next day. Luther’s opponents had reluctantly conceded to Luther even appearing, and they resisted any efforts to let Luther speak or explain his position. There was to be no debate. Confirming the pope’s condemnation and excommunication of Luther was their top priority. Yet the pressure on the emperor intensified as the proceedings went on. The request was granted and Luther was able to appear the next day on April 18.

The proceedings were always spoken in German and then repeated in Latin. Luther was asked the same question as the day before – if the books were his and if he would recant what he wrote. Luther was more prepared this time, and with greater confidence addressed the assembly. He said that his books fell into three categories. The first were Christian writings about faith and the Gospel which everyone agreed were good and godly. These he could not recant. The second category were writings against the abuses and tyranny by the pope and canon law against the German people. To recant these would be to allow the tyranny and godlessness against the German nation to continue. Many of the nobles in the room agreed wholeheartedly. The third category contained writings against persons or individuals who had attacked him or were defending the abuses. Here, Luther gave his sole concession that he may have spoken too harshly against them. However, since these writings also contained the word of God and the teaching of the Gospel, he could not recant these either.

Pressed one more time to answer clearly, Luther replied in a quiet voice, first in German, then in Latin.

“Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not retract anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. I can do no other. Here I stand. May God help me. Amen.”

After Luther was escorted from the chamber, he felt a great relief, and told his supporters, “I’ve come through!” Luther had emerged on the stage of world history, and everyone was solidifying their opinions of this man and the movement. The estates discussed the matter with the emperor on April 19 and 20. They were greatly concerned about public uprisings and took a softer stance than the emperor and church officials. On April 22 they were given three days to try and resolve the matter with Luther. A committee from the estates met with Luther. While the estates tried to focus on Luther’s attitude and behavior, Luther called for a council to settle the doctrinal disputes on the basis of Scripture. All the points of the previous days were repeated and no solution could be reached. Luther asked for safe protection from the emperor and the opportunity to defend his teachings on the basis of Scripture. Any way forward, for Luther, must recognize the sole authority of the Scriptures.

On April 25, Luther was officially informed that the emperor, as protector of the church, would be taking action against him, and that he had 21 days to safely return home before the promise of protection ended. Luther was forbidden to preach, write, or stir up the people in any other way. Luther’s opponents would use the time to officially publicize the proceedings against Luther and make their case against him. The Edict of Worms, condemning Luther as a heretic, would be dated May 8 and published May 25. Luther shook the hands of the officials, and thanked the estates and the emperor for hearing him, and complained only that his case was not addressed on the basis of the Scriptures. Again, the word was paramount.

Luther set out from Worms with his companions on April 26 and retraced his steps on the journey to Wittenberg. After his stay in Eisenach, on May 4, Luther and two companions were traveling to visit friends nearby when they were ambushed by men on horseback with crossbows. Luther was thrown into a wagon and kidnapped by these men, and whisked away. The plot had been put in place by Luther’s friends who took Luther secretly to the Warburg Castle, near Eisenach, where Luther would remain in hiding for over 10 months in absolute secrecy. This was to ensure Luther’s safety and see how things would unfold after the events in Worms. From the confines of the Wartburg, with many wondering if Luther was dead or alive, Luther would continue the work of reforming the church until March, 1522, translating the New Testament into German, and spending time in prayer and writing. Subsequent events will be commemorated in future 500 year anniversaries.

Luther set out from Worms with his companions on April 26 and retraced his steps on the journey to Wittenberg. After his stay in Eisenach, on May 4, Luther and two companions were traveling to visit friends nearby when they were ambushed by men on horseback with crossbows. Luther was thrown into a wagon and kidnapped by these men, and whisked away. The plot had been put in place by Luther’s friends who took Luther secretly to the Warburg Castle, near Eisenach, where Luther would remain in hiding for over 10 months in absolute secrecy. This was to ensure Luther’s safety and see how things would unfold after the events in Worms. From the confines of the Wartburg, with many wondering if Luther was dead or alive, Luther would continue the work of reforming the church until March, 1522, translating the New Testament into German, and spending time in prayer and writing. Subsequent events will be commemorated in future 500 year anniversaries.

For further reading and sources:

Roland H. Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther, Abingdon Press, Nashville, 1977

Martin Brecht, Martin Luther His Road to Reformation 1483-1521, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, 1985

James Kittelson, Luther the Reformer: The Story of the Man and His Career, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, 2003

Eric Metaxis, Martin Luther: The Man Who Rediscovered God and Changed the World, Viking, New York, 2017

Frederick Nohl, Martin Luther: Biography of a Reformer, Concordia Publishing House, St. Louis, 2003