Christmas Devotion

Gather your family and friends together for this Christmas devotion. Take some time to read the scripture, the reflection, and ask the question after each section.

“Do not be afraid, Mary; you have found favor with God. You will conceive and give birth to a son, and you are to call him Jesus.” – Luke 1:30-31

This Christmas season, we remember the true reason for the season, Jesus. Not the toys and shopping, not the carols and eggnog, but Jesus. Jesus, Our Lord and Savior who humbled himself to be born of a virgin. As we look to the nativity scene of Jesus birth, we take a look at Mary, Jesus, and the shepherds.

While this was a strange visit from an angel, Mary’s response in Luke 1:38, “I am the Lord’s servant,” was one showing she trusted in God. While it may always seem strange how the Messiah, the promised one, Jesus came into this earth, we thank God for His work through Mary.

Ponder this question together; in what ways can we be ‘servants of the Lord’, to those around us?

Jesus

“She will give birth to a son, and you are to give him the name Jesus, because he will save his people from their sins.” – Matthew 1:21

The name Jesus, literally means Savior, or the one who saves. Jesus came into this world to do just that, save us from our sins. Jesus, the Son of God, took on human flesh to save us. Not only was he true man, but also still true God. Jesus, as true God, humbled himself to take on human flesh, to be the ultimate sacrifice for the sins of all.

Go around to a few people at your gathering and ask this question: Why is Jesus the reason for the season?

Angels & Shepherds

“And there were shepherds living out in the fields nearby, keeping watch over their flocks at night.” – Luke 2:8

The lowly shepherds. Common folk. Normal guys. These were the first ones that the angels proclaimed the good news to. Not to the royalty, not to the chief priests and scribes, but the shepherds. The birth of the Christ child, Jesus, is announced to a group of shepherds, regular people, who were just going about their daily life.

Take some time, and ask this question: What peace does it give that the angels proclaimed the birth of Christ to the shepherds first?

Prayer

Let us pray: Heavenly Father, you sent your Son Jesus into this world for all people. All races, all nations, every class, rich, poor, and we thank you for sending Jesus. Give us hearts of hope, peace, joy, and love this Christmas season. Amen.

Take some time and share prayer requests, and any way that you can be praying for all of those gathered with you, or those who are not able to be with you as well.

Dessert question:

How have you seen God working in your life this past year?

Thanksgiving Devotion

Rejoice always, pray continually, give thanks in all circumstances; for this is God’s will for you in Christ Jesus.

As you enjoy your Thanksgiving Holiday, we pray that you would take some time to use this devotion to remember what this holiday is truly about; Thanking God for everything with which He has blessed you and your family.

This writing from Paul reminds us about 3 actions that we are to do, rejoice, pray, and give thanks. As you think about those 3 actions, take some time with those that you are gathered with, and use this devotion to share how God is working and blessing you this Thanksgiving season.

Rejoice

“Rejoice in the Lord always. I will say it again: Rejoice!”

Philippians 4:4

Paul reminds us here that we are to rejoice always. This is not something new for Paul, as he also wrote our verse from 1 Thessalonians. Paul was even imprisoned when he wrote this letter, but was still rejoicing! While we may have troubles in this world, we can always find something worth rejoicing over in our lives.

Go around to a few people at your gathering and ask this question: In one word, what are you rejoicing about this Thanksgiving?

Pray

“And this is the confidence that we have toward him, that if we ask anything according to his will he hears us.”

1 John 5:14

John reminds us that we can have confidence as we go before our God, knowing that He hears us. Not only do we have the opportunity to pray, but God calls us to pray to him as our Father, and to go to Him with everything in prayer and petition. We can go to our gracious Heavenly Father about anything, anywhere, and anytime.

Take some time, and ask this question: What are you praying for this Thanksgiving?

Give Thanks

“Give thanks to the Lord, for he is good. His love endures forever.”

Psalm 136:1

Maybe you use this as a prayer after your meal for Thanksgiving, as a prayer that reminds us of the goodness of God. The Lord is indeed good. He has blessed us abundantly and sufficiently for all that we need in this world. His love for us never ends, and is shown in Him sending Jesus for us. That is something for which we are extremely thankful.

As you end your time of devotion take a few minutes, as time permits, to ask: Who else would you like to say thank you to this Thanksgiving?

Prayer

Let us pray: Gracious God, we give you thanks not just on Thanksgiving, but everyday. You are so good to us, and you have blessed us with so many great things. We thank You for everything that You have blessed us with, and ask that You would always remind us of your goodness and mercy. Amen.

Dessert question:

How have you seen God working in your life?

150th Anniversary of Trinity Lutheran

This year marks the 150th anniversary of Trinity Lutheran Church in Lansing. It is the oldest congregation in Lansing of the Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod, but not the oldest Lutheran church in Lansing or the surrounding area. The deep roots of Lutheranism in the Lansing area go back to early German immigrants who settled the land of the Grand River basin in the 1840’s and 50’s. Today all three major branches of the Lutheran Church are represented in Lansing, running food banks, community assistance programs, Lutheran schools, early childhood centers, campus ministries and international student outreach. This article will look at the early roots of Lutheran churches in the greater Lansing area and how they got established.

From Detroit and Ann Arbor, early German immigrants moved west and settled near Lansing, Westphalia, and Ionia. In 1853, a handful of German Lutherans from the Ann Arbor area began worshipping regularly in Lansing in people’s homes, only 6 years after Lansing became the capital of Michigan. They wanted to practice their faith according to the beliefs and customs of the Lutheran Church as they had them in the old country. They asked their former pastor from Ann Arbor, Rev. Fredrick Schmid (1807-1883) to serve them. He traveled to Lansing every few weeks to conduct services and administer the sacraments. Fredrick Schmid is a significant figure in Michigan history. He was the first pioneer Lutheran pastor in Michigan, arriving in 1833 to serve Lutheran settlers near Ann Arbor. From there he ministered to German Lutherans in Detroit, Saginaw, Monroe, and dozens of little towns and started over 20 churches. His remarkable and tireless ministry laid a solid foundation for the Lutheran church in Michigan, including Lansing.

In 1855 the Lutherans in Lansing organized themselves as Emmanuel First Evangelical Lutheran Church, now called Emmanuel Lutheran Church and School, located on N. Capitol Ave. They called a full time pastor, Christian Volz (1826 – 1883) who was a trainee of Pastor Schmid. He served only a short time and took a call to Buffalo, NY. Rev. Adam Buerkle (1825-1896) was then installed in 1857 and the church built a wood framed church near the present site in what was called “old Lansing” or “north Lansing.” Both pastors Volz and Buerkle served Lutherans scattered to the west of Lansing in Westphalia Township (who later formed St. Paul, Fowler in 1878) and Woodland (Zion Lutheran was organized 1856). In 1866, Emmanuel called Rev. John Her (1821-1905), of Bear Branch Junction, IN, to Lansing. The congregation’s growth was indicated by the building of a parsonage in 1867 and the establishment of a school in 1868. This school is today Emmanuel Lutheran School, although the congregation did not operate the school from 1927 to 1983.

In 1869, other Lutheran congregations were formed to the northwest of Lansing. St. Peter Lutheran Church and School was founded that year in Riley, and St. John’s Lutheran Church was founded in St. John’s. That year also brought trouble to the congregation in Lansing. Several sources indicate that Rev. John Her was accused of being heavy handed, abusing church discipline, and even acting improperly against the 6th commandment. The conflict erupted and the congregation asked the church body that they were affiliated with, the Ohio Synod, to investigate. The turmoil in the church had two major effects. First, they severed their ties to the Ohio Synod and joined the Michigan Synod, which today is the Michigan District of the Wisconsin Synod. Second, Rev. Her was removed from office and about fourteen families rallied around him and left Emmanuel on August 18, 1869. They worshipped in homes for a time and soon Rev. Her took a call to a congregation out east.

The families that had separated from Emmanuel were interested in forming a new congregation that was strong in doctrine and Lutheran practice, and appealed to the Missouri Synod for assistance. They met in homes and in the old city high school for a time, and reached out to Rev. H. Ramelow (b.1844) of Ionia. He was a seminary graduate who served a number of scattered Lutherans who lived the area in their homes. The Lutherans in Ionia and in Lansing called Rev. Ramelow simultaneously, and he was ordained and installed as pastor to both groups on August 20, 1871, by the LCMS pastor in Grand Rapids. Three weeks later, on September 10, 1871, with Rev. Ramelow presiding, Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church was formally organized. By the following year, Rev. Ramelow moved to Lansing as that was his only established congregation. A frame church was constructed and dedicated on January 7, 1872. School textbooks were purchased in April so that school could start in the fall. In June of that year, Trinity joined the Missouri Synod at their Milwaukee convention. That December, Rev. Ramelow took a call to Prairetown, IL, and was succeeded by Rev. J.M.M. Moll of Fraser, MI, who was installed February 2, 1873, by Pastor Georgii of St. Peter in Riley. That year the congregation also constructed a parsonage.

The two Lutheran congregations in Lansing were now firmly established and continued to grow. Although a German Lutheran Church was founded in nearby Grand Ledge in 1872, called Immanuel Lutheran, it was the Wisconsin Synod and Missouri Synod churches that had the deeper roots in Lansing. As the city of Lansing grew, the churches multiplied. Emmanuel First served as the ‘mother church’ for other church plants of the Wisconsin Synod, including Zion Lutheran Church on Pennsylvania Ave, which was founded as an English mission congregation in 1920, and later the suburban congregation in Delta Township, Shepherd of the Hills Lutheran, in 1975.

Trinity served as the ‘mother church’ for LCMS church plants in Lansing, including two daughter congregations in 1956 – Ascension Lutheran in East Lansing and Our Savior Lutheran Church and School on Lansing’s south side, which moved out to Delta Township in 2008. Christ Lutheran Church on Pennsylvania was founded in 1930’s as an English mission congregation, and today is part of St. Luke Lutheran Church, Haslett (which itself is a church plant of Ascension Lutheran). Martin Luther Chapel was started in East Lansing in 1954, and in 1964 both Good Shepherd Lutheran in Delta Township and St. Matthew Lutheran Church and School in Holt were organized. Messiah Lutheran in Holt was organized in 1978 by Our Savior and an influx of families from St. Matthew.

A Scandinavian Lutheran Church was organized in 1917, the 400th anniversary of the Lutheran Reformation, which paved the way for the third group of Lutherans in Lansing. The Scandinavian Lutheran Church changed its name in 1940 to Grace Lutheran Church. Redeemer Lutheran was founded as an English Lutheran Church in downtown Lansing in 1922, which had to relocate with the construction of I-496 to Lansing’s south side in 1962. Bethlehem Lutheran started in 1924 on Mt. Hope near Cedar Street. University Lutheran started in 1942 as a student association which eventually met in a movie theater before building a church and student center on Harrison Road near MSU campus. Suburban expansion saw the formation of St. Stephen Lutheran on north Waverly, Faith Lutheran in Okemos, and Calvary Lutheran in Delta Township, all in 1956. Calvary closed in 2021. St. Paul Lutheran was organized in East Lansing in 1965.

In 1900, there were only two Lutheran churches in Lansing – Emmanuel First and Trinity, and the country churches of Immanuel, Grand Ledge, St. John, St. John’s, and St. Peter, Riley. A century later, in the year 2000, there were 21 Lutheran churches in the greater Lansing area, each striving to proclaim the Gospel of Jesus Christ. The stories of each congregation reveal the successes and struggles of church life, all under grace, and the faith-filled individuals who tirelessly served God by building up the Kingdom of the Lord. Collectively, the histories of these churches serve as inspiration and lessons for continuing the work of congregation ministries today. May God preserve His word and sacraments among us as He did for our forefathers, and may we continue to live under His amazing grace and to share His unconditional love with the greater Lansing area and beyond.

What was the Reformation?

By Pastor Bill Wangelin

Today, we are familiar with a Christianity that focuses on the grace and love of Jesus Christ and on the Bible as the Word of God and the basis for our faith and life. It may surprise you, but that was not always the case throughout church history.

During the Middle Ages, the Christian Church in Europe was so corrupted by a mingling of church and state that the basics of the Christian faith were obscured and neglected. The common people knew nothing of God’s love or the free gift of salvation through faith in Jesus Christ. Most people had never seen a Bible, let alone read one. And major fundraising efforts in the church were conducted by selling the forgiveness of sins through certificates called “indulgences.” Church leaders neglected spiritual duties and pursued worldly wealth and power. All sorts of invented ideas and superstitions were taught by priests and pastors. The church was in major need of recalculating, recalibrating, and reforming.

On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther took a stand and pushed back against church authorities in a call to reform the Christian Church. On that date, he posted the 95 theses, or statements for debate, over how the church claimed people could purchase the forgiveness of sins through the purchasing of certificates called “indulgences.” This marked the beginning It’s not about the man; it’s about the message, that we are saved by grace alone through faith alone on account of Christ alone. What was the Reformation? by Pastor Wangelin of a debate that he would champion, that the Christian Church should ultimately be about faith in Christ, and based solely on the Word of God.

As Martin Luther read the Bible, he came to the realization that we cannot purchase the forgiveness of sins, nor can we earn it by any good works. We are saved solely by God’s grace, and solely through faith. With the support of his prince, Martin Luther and his colleagues at the University of Wittenberg began applying these truths to all areas of the church’s faith and life. This is what the Lutheran reformation was all about.

The Reformation Changed the World

There were other efforts at reform prior to Martin Luther. In previous centuries, most of them were limited and ended with someone being burned at the stake. But because Luther’s prince was a powerful figure at the time, and because the newly invented printing press helped Luther’s writings go viral, the Lutheran reformation set off a chain reaction in many countries. Reformations in Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands, England, and Scandinavia soon followed, and other “protestant” churches such as the Reformed, Anglican/Episcopalian, Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist, and others can trace their roots back to the ideas initiated on the Wittenberg castle church door.

The Lutheran reformation also led to major reforms in government, education, art and music. Martin Luther is both the founder of Lutheran schools and also the public school system. The individualism of the reformation led to American democracy. In this way, the reformation was of global significance, and Martin Luther was named the man of the millennium in 2000.

We know that Martin Luther was no saint, and we lament his sins and shortcomings. But the movement was not about the man, it was about the message, and that was the message of the Gospel – the good

news that we are saved by grace alone, through faith in Christ alone, as declared by Scripture alone. The reformation was all about Jesus! As we celebrate the reformation, we recommit ourselves to the truths of the Gospel, and the authority of Scripture, and God’s desire that all would come to saving faith in Him. To learn more about the Reformation, go to www.lutheranreformation.org.

Cremation and the Christian Body

A Guide for Christian Burial Practices

By Pastor Bill Wangelin

More Christians are choosing cremation as a burial option for a number of reasons. Some choose it for financial reasons, some for practical reasons, and some because it is more socially acceptable. Cremation was not historically an option for Christians, so there are not a lot of longstanding Christian customs or traditions with regards to cremation. What should Christians consider when it comes to cremation of a Christian? Our actions and customs around death and burial say something about our belief in what comes next. Christians have a lot to profess when it comes to life after death in light of Jesus’ resurrection. The following hopes to serve as a guide to help Christians make godly decisions about how we treat the deceased human body.

There is nothing in the Bible that forbids cremation. The church cannot make any new laws or commands that would burden people’s consciences. The Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod has no official position on the matter. However, as Christians, we seek best practices that are informed by our faith and that give witness of our faith to the world.

What is Cremation?

In cremation, the body is burned until only the bones remain. These are then ground up into a powder with the ashes, and the remains placed in a container. It should be noted that in the cremation mechanism, not all the remains can be thoroughly extracted, so some of the ashes remain in the machine, and some ashes from previous cremations may be mixed in with others. The ashes are then given to the family for their use. Legally, the ashes are no longer considered a human body, as the body has been thoroughly destroyed.

People do all sorts of things with the ashes from cremation, and more creative uses are being discovered every day. Some are placed in an urn and put on a shelf in a home. Some are pressed into diamonds and worn as jewelry. Others are scattered in a field or body of water, or placed in coral reefs. The possibilities are endless.

Why did Christians historically not practice cremation?

Christians (and Jews) believe in a resurrection of the body, that our body is a gift from the Lord and part of his good creation. Jesus taught that when He would come again, our bodies would be raised up to eternal life. Jesus demonstrated this in His own resurrection, when He showed His disciples that He was not a ghost, but had flesh and bones that they could touch and feel. Likewise, our bodies are now a temple of the Holy Spirit, and will be raised up on the last day. The Christian hope is not merely that our souls go to heaven when we die, but that our bodies will be raised to life on the last day. Christians consequently value the human body more than any other religion or philosophy.

Greek and Roman pagans did not believe in a resurrection of the body, but that a person’s body had no use after death. This was demonstrated by burning the body and scattering the ashes, to show the utter disappearance of the person.

In the Bible, burning is always a picture of judgment, and is associated with the fire of hell. Thus, in the Middle Ages, heretics were burned to show their judgment by God, and to burn someone’s body was to deny the possibility of their resurrection to eternal life.

How do Christians treat the dead body of a Christian?

Jesus (and St. Paul) resisted speaking of the dead as dead. Notably, Jesus referred to Jairus’ daughter (Luke 8:49-56) and His friend Lazarus (John 11:11) as “sleeping.” St. Paul talks about those who have “fallen asleep” until Christ’s return, when their bodies will wake up to eternal life. The biblical word for death is “sleep” because those who are sleeping wake up! In addition, St. Paul speaks of how the natural body is “sown” before it is raised a spiritual body (1 Corinthians 15:42-44. It is sown a perishable body and raised an imperishable body. It is sown in weakness and raised in glory. The image is that the body is like a seed that is planted in the ground, dead in appearance, yet sprouts to new life. How would a Christian have their body prepared for burial with this Biblical language in mind?

In the Old Testament, the people of God had tombs where people’s bodies were laid to rest. The Old Testament phrase is “He rested with his fathers, and was buried…” Their existence was marked and remembered, and their bodies were honored. We also remember that our Lord Jesus was laid in a tomb before His resurrection. Christians have continued this practice, carefully preserving the body and marking its existence and resting place, where it would wait for the return of Christ.

A Christian funeral makes reference to the resurrection of the body, not merely that the soul is with Jesus. We take comfort in knowing that at the moment of death, our loved ones are “with the Lord.”(Philippians 1:23). But it would be incomplete to ignore the promise of the resurrection of the dead, of which Christ is the first fruits (see 1 Corinthians 15).

Can God Raise Ashes?

There is no doubt that God can raise a body from the dead after it has been cremated. When Christ returns, the sea will give up it’s dead, and all who sleep in the dust of the earth will awake – even those bodies who have been turned to dust (as most bodies have). Daniel 12:2 says “those who sleep in the dust of the earth” will awaken to eternal life. The power of God is so great that he can raise up and restore to life any body, in any shape, in any place.

The issue then, is not about the power of God to raise the cremated body, but the witness of our faith that is given in how we treat the deceased body of a Christian, cremated or otherwise. How is our Christian faith made evident in our burial practices?

What About Cremation for Christians?

If a Christian decides to have their body (or the body of a loved one) cremated, then they need to consider how to demonstrate our faith in “the resurrection of the body and the life of the world to come” in the way they treat the cremated remains of a Christian. They should honor the body remains and lay them properly to rest until the return of Christ when they will be raised from the dead.

Here are some ways that a Christian body that has been cremated can be honored in accordance with our Christian faith:

- A Christian memorial service should be held that clearly professes the resurrection of the body and Jesus’ victory over death at his resurrection.

- The ashes should be kept together (not separated or scattered) and buried in the ground or placed in a columbarium or memorial garden.

- The final resting place should be marked with the person’s name in memory of that person.

- When the ashes are laid to rest, there should be a clear message of hope in the resurrection, just as in a committal graveside service, as the ashes are commended into the hands of God in the hope of the resurrection.

These four guidelines, along with counsel and guidance from your pastor, should serve Christians well as we adapt our burial customs yet cling to the same message of hope that we have in our resurrected and living Lord Jesus. Pastoral care will provide more wisdom on how to navigate the grieving process and look to the Lord for comfort and consolation. More and more, our customs and actions make us distinct from the rest of the world, and those who “grieve like the rest of men, who have no hope.” Christ has been raised from the dead, and so we stand in a living hope of our future with Him, and confidently profess our believe “in the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come.” Amen. Come, Lord Jesus!

Postscript: The four guidelines for Christian cremation practices were the reason for creating the Memorial Garden at Our Savior Lutheran Church, Lansing, Michigan. After observing cases where one or more of these guidelines were not followed, the church created a means to direct the faithful to faithful practices of Christian burial that are more consistent with our past practice and common confession of faith. For information on the memorial garden, go to www.oursaviorlansing.org/memorialgarden.

How does the Lord’s Prayer End?

By Pastor Bill Wangelin

By Pastor Bill Wangelin

“For Thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory, forever and ever. Amen.”

Is that really part of the Lord’s Prayer? It depends on which church you ask.

A few years ago, my wife and I attended the wedding for our neighbors who are Roman Catholic. The service had a number of familiar elements to us, including the prayers for the couple and for families. When they started the Lord’s Prayer, we jumped right in and spoke it along with them. However, as we prayed, our elbows began hitting each other and nudging each other. We both knew that Roman Catholics ended the Lord’s Prayer earlier than Lutherans. With these marital reminders, we both remembered to say “… but deliver us from evil. Amen.”

Inevitably, a number of fellow protestants in the congregation inadvertently exposed themselves by saying “For Thine is the kingdom and the…” and then sheepishly went silent. We smiled as we identified in that moment our fellow protestants in the congregation and successfully navigated that cross-denominational pitfall.

Why do some Christians say the conclusion to the Lord’s Prayer and others don’t?

Many are surprised to learn the conclusion was not part of the original Lord’s Prayer as Jesus taught it to His disciples, as documented in the earliest manuscripts of the New Testament. Matthew chapter 6 and Luke chapter 11 are the two places where Jesus’ teaching on the Lord’s Prayer is found. When one compares the two in modern translations, they notice that there are slight variations in wording (Matthew has ‘forgive us our sins’ and Luke has ‘forgive us our debts’) and the conclusion is overtly missing in each instance. What do we make of this?

It can be firstly noted that Jesus gave His disciples the Lord’s Prayer as an example of how to pray – not as a fixed formula that we have to get ‘exactly right.’ The fact that Matthew and Luke record variations in the prayer demonstrates that. If Jesus taught publicly for over three years in towns all over Judea, Samaria, and Galilee, how many times do we think Jesus taught the Lord’s Prayer? Matthew’s “Sermon on the Mount” and Luke’s “Sermon on the Plain” are likely transcripts of two different occasions, as Jesus must have repeated His teachings countless times in different settings. This accounts for a number of the differences between the Gospels.

Secondly, since the Lord’s Prayer is the standard that Jesus gave, it is the prayer par excellence, and asks God for what we need the most. It was taught by the disciples to others, and the earliest Christian communities used this prayer in their worship services. It is attested to the earliest of Christian writings, such as the Didache from ca. 100 AD. More on that later.

In the NIV and ESV translations of Matthew chapter 6 (and in many others) there is a footnote at the end of the Lord’s Prayer. It says, “some late manuscripts add ‘For yours is the kingdom and the power and the glory forever and ever, Amen.’

Although we don’t have the original pieces of paper that the Gospel writers and apostles signed (called the original autographs), there are over 5,000 ancient manuscripts of the New Testament that scholars have studied and compared to determine the accurate text of the original writings. It is absolutely astounding how coherent and unified the text is with all those copies. The words were carefully copied and passed down through the generations, and we can be confident in the reliability of the text and translations we use today. While there are numerous little discrepancies among the 5,000 ancient manuscripts (such as one manuscript saying ‘Christ Jesus’ and another saying instead ‘Lord Jesus Christ’) there are only a handful of places where there is any significant change in meaning. Modern translations are open and transparent about that, and note those discrepancies in the footnotes. The note after the Lord’s Prayer is a good example of this.

The footnote at the end of the Lord’s Prayer in Matthew 6 indicates that the conclusion to the Lord’s Prayer was not part of the original Gospels. However, it also shows that this concluding doxology was used very early on in the Christian communities, as a part of their liturgical and worship life. By identifying the “late manuscripts” we can estimate the time period when the conclusion was added to the Lord’s Prayer.

In researching this, I was surprised to learn that the conclusion to the Lord’s Prayer is earlier than I imagined, and that it was regularly used in the Lutheran Church much later than I realized.

The study of Biblical manuscripts can be a technical and academic exercise, and allow scholars to really dig deep into this area of Biblical studies. Searching for the origins to the conclusion to the Lord’s Prayer leads us down this path. This road will get rather detailed as we dig deeper. Are you ready?

The Conclusion in Biblical Manuscripts

The oldest manuscripts for the New Testament are papyrus pages and early books called a codex. The oldest manuscripts of the Gospel of Matthew, for example, are codex Sinaiticus, codex Vaticanus, codex Dublinensis, etc. (The names of the codex are based on either their place of origin or their current location). These early manuscripts end the Lord’s Prayer in Matthew 6:13 with “but deliver us from evil.” and do not include the conclusion. This is the evidence that most Biblical scholars point to for the original version of the Lord’s Prayer without the conclusion.

In the 380’s, St. Jerome produced a Latin translation of the Bible, called the Vulgate. He looked at the original languages of Hebrew and Greek for the Old Testament and New Testament translations respectively. He noticed that the older manuscripts of the New Testament did not have the conclusion to the Lord’s Prayer, and so it is not included in the Latin Vulgate. This became the official translation of the Roman Catholic Church in the 1500’s, and that is a main reason why the Roman Catholic Church has never really used the conclusion to this day.

The oldest mention of the conclusion to the Lord’s Prayer is actually not a Biblical manuscript, but what may be the oldest Christian document we still have, called “The Teaching of the Twelve” or “The Didache.” The Didache dates to around 100 A.D., and possibly earlier, which puts it within reach of the apostolic age and the earliest Christian churches that they founded. It mentions baptism, the Lord’s Supper, and the Lord’s Prayer. It concludes by saying, “but deliver us from evil. For yours is the power and the glory forever, Amen.”

The oldest codex that includes the conclusion is Codex Washingtonensis. You might guess that it is housed in the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C. It is dated from 300 – 500 A.D., which is a little later than the manuscripts mentioned above, but still very early. It’s place of origin is Egypt. It has in Matthew 6:13, “but deliver us from evil. For yours is the kingdom and the power and glory forever and ever, Amen.”

Later Greek copies of Matthew’s Gospel included the text of Washingtonensis, and these became the family of manuscripts that were known as the Byzantine family of texts, copied and reproduced through the centuries out of Constantinople. This version became known as the “Majority Text” since there were so many Greek copies. We can also find the conclusion to the Lord’s Prayer in the Syriac translation and Coptic translations. That made the conclusion very widespread in countless Christian communities (non-Roman Catholic) and editions of the New Testament (non-Latin) for the past 1,500 years.

When the Bible was translated into English by John Wycliff, he had only the Latin Vulgate to rely on, so his translation around 1390 did not include the conclusion in Matthew 6:13. However, when later protestant groups produced the English Geneva Bible in 1560 and the King James Bible in 1611, they based their translations on the Greek texts, rather than the Latin. They used the Majority Text, which included the conclusion to the Lord’s Prayer. Through the King James Version, the conclusion to the Lord’s Prayer was firmly anchored in English protestant churches for the past 400 years.

The Conclusion in the Lutheran Church

Martin Luther translated the Bible during a time when scholars were going ‘back to the source’ and using original languages. He, too, relied on the Greek Majority Text that included the conclusion to the Lord’s Prayer, and so it shows up in his translation of Matthew 6:13.

However, when Martin Luther wrote the Small Catechism, he did not include the conclusion! The last petition is “deliver us from evil” with its explanation, and then comes simply “Amen” with its explanation. A version of the small catechism printed after Luther’s lifetime in Nurnberg 1584 is the first one to insert “For Yours is the kingdom and the power and the glory forever and ever” just before the word “Amen.” Catechisms of other denominations added the conclusion and wrote an explanation to it. While the conclusion was omitted in most editions of the Catechism, an 1816 translation into English by Rev. Dr. Phillip Mayer included it like the Nurnberg edition, and the Mayer translation served as the basis for nearly all English translations of the Small Catechism in the US through the 1800’s.

The German catechisms of the Missouri Synod in the 1800’s and early 1900’s did not include the conclusion to the Lord’s Prayer. It was not until the catechism was produced in English that the conclusion was included. It appears in the 1943 Luther’s Small Catechism and every English translation since, even though the explanation only references the one word “Amen.”

In the liturgy of the Lutheran Church, there developed two forms – the Morning Service (without Communion) and the Service of Holy Communion. The morning service, especially in the US, had the congregation speak the Lord’s Prayer together, including the conclusion. In the Communion Service, however, the Lord’s Prayer was spoken by the pastor, up until the phrase “but deliver us from evil.” At that point, the congregation continued in song with “For Thine is the Kingdom and the Power and the Glory forever and ever. Amen.” This is how the Lord’s Prayer is presented in later German liturgies of the Missouri Synod hymnals, and in English hymnals such as The Lutheran Hymnal of 1941 (and its continuation as Divine Service Setting Three in Lutheran Service Book.), the Service Book and Hymnal of 1958, Lutheran Book of Worship (1978) and Lutheran Worship (1982). So, even though Martin Luther included the conclusion to the Lord’s Prayer in his translation of the Bible, the Catechisms and Lutheran Liturgy did not fully embrace it until the mid 1900’s.

It may be that the inclusion of the conclusion was a result of the transition in the Missouri Synod from German to English. When translating liturgical texts and hymnody, there was a tendency to borrow from the churches which were already using English in their worship, and which used the conclusion to the Lord’s Prayer. The more English the Lutheran Church became, the more it used the full version of the Lord’s Prayer with the conclusion.

Differences in Denominations

We’ve followed the path that the conclusion to the Lord’s Prayer made from the early Christian communities into our worship and prayer life today. Roman Catholics and Lutherans use it differently. It can also be noted that the Reformed Churches say the Lord’s Prayer slightly differently than Lutherans (“For Thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory forever. Amen.”) Other churches have updated the language to say “Your kingdom come. Your will be done…” (Lutheran Book of Worship 1978). There are some significant doctrinal differences between the various Christian denominations, and these need to be taken seriously. However, thanks be to God, the differences with the Lord’s Prayer is not one of them! It makes no difference which version we use, and we can affirm all Christians in praying the prayer Jesus taught us to pray – with or without the conclusion.

In some cases, the differences are an annoyance and highlight our divided Christendom. However, they can also be an opportunity to talk about our various church customs and traditions, what we really believe, and where we really have the common ground that matters. The Lord’s Prayer is part of that common ground that we can celebrate and elevate.

What does this mean?

Even though the conclusion to the Lord’s Prayer is not addressed in the Small Catechism, and although it is not originally part of the Bible, it is very biblical in its content. These words are rich with biblical meaning of both Old and New Testaments that aptly bring glory and praise to our God, whom we are privileged to call “Our Father” through His Son, Jesus Christ. The traditional term for an expression of glory and praise is “doxology.” The Common Doxology is often sung to conclude a service or church meeting – “Praise God from Whom all blessings flow! Praise Him all creatures here below! Praise Him above ye heavenly hosts! Praise Father, Son and Holy Ghost. Amen.”

The Scriptures are filled with doxologies as God’s people are moved to give glory and praise to God for who He is and what He has done. In Revelation 7 we have the great doxology of the multitude gathered around the throne (kingdom) worshipping God and saying, “Amen! Praise and glory and wisdom and thanks and honor and power and strength be to our God for ever and ever. Amen!” In Revelation 19 the multitude shouts, “Hallelujah! Salvation and glory and power belong to our God… Hallelujah! For our Lord God Almighty reigns. Let us rejoice and be glad and give him glory!”

In Daniel chapter 7, the prophet received a vision of the Messiah, whom he saw as the Son of Man coming on the clouds of heaven and approaching the Ancient of Days. It says, “He was given authority, glory and sovereign power; all nations and peoples of every language worshiped him. His dominion is an everlasting dominion that will not pass away, and his kingdom is one that will never be destroyed.” This passage mentions the kingdom, the power, and the glory that belongs to God also ascribed to the Messiah (because He is God).

When the offerings were gathered for the temple, King David prayed in 1 Chronicles 29:11, “Yours, Lord, is the greatness and the power and the glory and the majesty and the splendor, for everything in heaven and earth is yours. Yours, Lord, is the kingdom; you are exalted as head over all.” This is perhaps the closest Scripture passage that ascribes to God the kingdom, the power, and the glory forever.

The conclusion to the Lord’s Prayer continues in the Christian church as a fitting statement of faith and praise, to which we can fully say, “Amen.” It is a rich and biblical part of our liturgical heritage, embedded into our prayer and worship life that ascribes to God His greatness, His goodness, and His saving kingdom that we pray would come among us also. To God be the glory!

Luther at the Diet of Worms

The 500th anniversary of the Reformation in 2017 was a momentous milestone that commemorated Martin Luther sparking the Reformation through the posting of the 95 Theses on the castle church door on October 31, 1517, in Wittenberg, Germany. The impact of that event and its consequences were certainly not known at that time, but unfolded through the Reformation movement in the following years. We are following those events 500 years later and reflecting on the consequences and blessings.

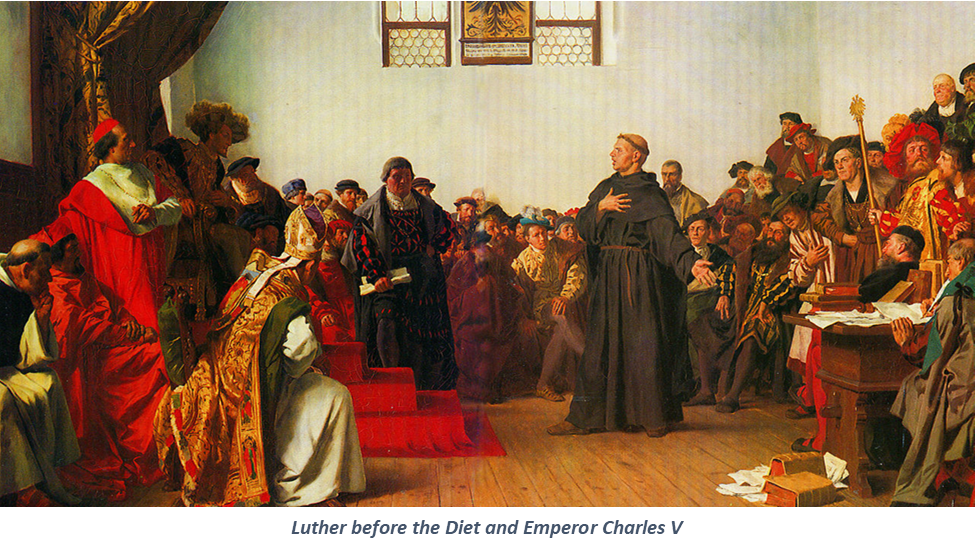

Perhaps one of the most significant moments of the Reformation, and certain in Luther’s life, was his appearing before the Congress of the Holy Roman Empire, before counts and nobles, princes and electors, and the Holy Roman Emperor himself, the young Charles V. What Luther said at this moment would set the Reformation on an irreversible course against the forces of the pope and emperor. This was the moment of decision where Luther’s faith in God and his conviction that the Scriptures were the highest authority in the church would lay the foundation for the Reformation movement.

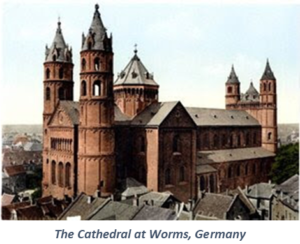

The imperial congress, called a Diet, was held in the city of Worms (pronounced “Vohrms”), one of most ancient cities in Germany. This is where we get the name of this event, called the Diet of Worms. It was a four month long gathering of the top levels of government in the Holy Roman Empire – nobles, knights, counts, and free cities called “The Estates” and the top rulers called “The Electors,” which included three archbishops and also the Prince Elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise, who was Luther’s protector.

The imperial congress, called a Diet, was held in the city of Worms (pronounced “Vohrms”), one of most ancient cities in Germany. This is where we get the name of this event, called the Diet of Worms. It was a four month long gathering of the top levels of government in the Holy Roman Empire – nobles, knights, counts, and free cities called “The Estates” and the top rulers called “The Electors,” which included three archbishops and also the Prince Elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise, who was Luther’s protector.

The Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, was from the Spanish line of the Hapsburg family, and was only 21 at the time. In fact, this was his first imperial diet, and all eyes were on the young emperor as he had to grapple with internal and external threats from France, from the pope, from the Muslim armies advancing into Europe, and now a theological dispute with a little German monk that threatened the unity that his empire needed precisely at this moment.

After Luther started the debate about indulgences in 1517, the discussions focused on the nature of the Gospel (saved by grace through faith alone – not by works) and the authority of the Scriptures (which Luther claimed were infallible, unlike popes and councils, which could err). As Luther promoted his ideas at the Heidelberg Disputation in 1518 and the Leipzig Debate with John Eck in 1519, his attacks against the church hierarchy over the abuses they tolerated and the false doctrine they promoted reached the ears of the archbishops and the pope himself. Luther’s key writings in 1520 (On the Freedom of a Christian, the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, and Address to the Nobility of the German Nation) caused so much public antagonism to Rome that some feared a mass uprising. These writings were the last straw. Several church leaders in Germany made it their goal to squash the debates caused by Luther and reinforce the authority of the church. They succeeded in having Luther excommunicated by the pope in January, 1521. They pressed the emperor to ratify the pope’s decree with a civil injunction against Luther, showing the unity of church and state against heretics. This was to be taken up by the Diet in Worms.

In a strange twist of events, including a delicate dance of politics, piety, and diplomacy, the influence of Fredrick the Wise and Luther’s supporters managed to somehow change the course of the proceedings, so that rather than simply condemn Luther, he should be brought forward to give an opportunity to speak. Some thought this was playing with fire, as it might give the heretic an opportunity to further spread his teachings and foment the disgruntled public against Rome. Eventually, the emperor agreed to have Luther summoned to Worms, and sent his herald to personally fetch Luther from Wittenberg, about 325 miles away.

The herald reach Wittenberg on March 29, and on April 2, Luther set out in a covered wagon with his companions. Their journey to Worms in some ways felt like a death march, where Luther was following in the footsteps of other reformers like John Hus and John Wycliffe, who were condemned and burned. Would Luther go to the flames? He wrote to his friends that he was prepared to give his life for his faith and the cause of Christ. On the other hand, the journey was like a victory parade for a celebrity, and a march of triumph where Luther was greeted by throngs of people who had read his writings and felt like he was some sort of savior to the German people. He was resisting the vile Roman abuses in Germany and protecting the hearts and livelihood of the people. Luther was portrayed as a German Hercules, and pictures and prints appeared that represented violent aggression against the Roman church leaders. Some were moved by faith and piety, some were moved by patriotism and populism. Luther knew where his heart and faith were grounded – in God’s Word and the sake of the Gospel, and he felt that in some ways his journey to Worms was like Christ’s procession into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, with cheering crowds and a cross before him.

After journeying through towns and cities such as Leipzig, Weimar, Erfurt, Eisenach, and Frankfurt, Luther and his entourage entered Worms on April 16 to the sound of trumpets and crowds of several thousand. The pressure was on the Diet to deal with the Luther matter delicately. The dignitaries in Worms lined up to meet personally with Luther and give him encouragement.

The next day, April 17, Luther was brought into the hall before the assembled diet. He had to be escorted through back doors and passageways because of the crowds outside. As a monk, Luther had not been exposed to such worldly pomp and circumstance. He looked all around the hall and even smiled and waved at people he recognized, and was consequently scolded by the imperial marshal. Luther was not accustomed to the ways of the courts and nobility. As soon as Charles saw Luther, he said “He will not make a heretic out of me.”

The next day, April 17, Luther was brought into the hall before the assembled diet. He had to be escorted through back doors and passageways because of the crowds outside. As a monk, Luther had not been exposed to such worldly pomp and circumstance. He looked all around the hall and even smiled and waved at people he recognized, and was consequently scolded by the imperial marshal. Luther was not accustomed to the ways of the courts and nobility. As soon as Charles saw Luther, he said “He will not make a heretic out of me.”

Luther’s books were in a pile in the middle of the room, and Luther was asked if he would recant what he had written. He replied that the writings were indeed his own, but since they contained matters of faith and the Word of God, he asked to respond the next day. Luther’s opponents had reluctantly conceded to Luther even appearing, and they resisted any efforts to let Luther speak or explain his position. There was to be no debate. Confirming the pope’s condemnation and excommunication of Luther was their top priority. Yet the pressure on the emperor intensified as the proceedings went on. The request was granted and Luther was able to appear the next day on April 18.

The proceedings were always spoken in German and then repeated in Latin. Luther was asked the same question as the day before – if the books were his and if he would recant what he wrote. Luther was more prepared this time, and with greater confidence addressed the assembly. He said that his books fell into three categories. The first were Christian writings about faith and the Gospel which everyone agreed were good and godly. These he could not recant. The second category were writings against the abuses and tyranny by the pope and canon law against the German people. To recant these would be to allow the tyranny and godlessness against the German nation to continue. Many of the nobles in the room agreed wholeheartedly. The third category contained writings against persons or individuals who had attacked him or were defending the abuses. Here, Luther gave his sole concession that he may have spoken too harshly against them. However, since these writings also contained the word of God and the teaching of the Gospel, he could not recant these either.

Pressed one more time to answer clearly, Luther replied in a quiet voice, first in German, then in Latin.

“Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not retract anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. I can do no other. Here I stand. May God help me. Amen.”

After Luther was escorted from the chamber, he felt a great relief, and told his supporters, “I’ve come through!” Luther had emerged on the stage of world history, and everyone was solidifying their opinions of this man and the movement. The estates discussed the matter with the emperor on April 19 and 20. They were greatly concerned about public uprisings and took a softer stance than the emperor and church officials. On April 22 they were given three days to try and resolve the matter with Luther. A committee from the estates met with Luther. While the estates tried to focus on Luther’s attitude and behavior, Luther called for a council to settle the doctrinal disputes on the basis of Scripture. All the points of the previous days were repeated and no solution could be reached. Luther asked for safe protection from the emperor and the opportunity to defend his teachings on the basis of Scripture. Any way forward, for Luther, must recognize the sole authority of the Scriptures.

On April 25, Luther was officially informed that the emperor, as protector of the church, would be taking action against him, and that he had 21 days to safely return home before the promise of protection ended. Luther was forbidden to preach, write, or stir up the people in any other way. Luther’s opponents would use the time to officially publicize the proceedings against Luther and make their case against him. The Edict of Worms, condemning Luther as a heretic, would be dated May 8 and published May 25. Luther shook the hands of the officials, and thanked the estates and the emperor for hearing him, and complained only that his case was not addressed on the basis of the Scriptures. Again, the word was paramount.

Luther set out from Worms with his companions on April 26 and retraced his steps on the journey to Wittenberg. After his stay in Eisenach, on May 4, Luther and two companions were traveling to visit friends nearby when they were ambushed by men on horseback with crossbows. Luther was thrown into a wagon and kidnapped by these men, and whisked away. The plot had been put in place by Luther’s friends who took Luther secretly to the Warburg Castle, near Eisenach, where Luther would remain in hiding for over 10 months in absolute secrecy. This was to ensure Luther’s safety and see how things would unfold after the events in Worms. From the confines of the Wartburg, with many wondering if Luther was dead or alive, Luther would continue the work of reforming the church until March, 1522, translating the New Testament into German, and spending time in prayer and writing. Subsequent events will be commemorated in future 500 year anniversaries.

Luther set out from Worms with his companions on April 26 and retraced his steps on the journey to Wittenberg. After his stay in Eisenach, on May 4, Luther and two companions were traveling to visit friends nearby when they were ambushed by men on horseback with crossbows. Luther was thrown into a wagon and kidnapped by these men, and whisked away. The plot had been put in place by Luther’s friends who took Luther secretly to the Warburg Castle, near Eisenach, where Luther would remain in hiding for over 10 months in absolute secrecy. This was to ensure Luther’s safety and see how things would unfold after the events in Worms. From the confines of the Wartburg, with many wondering if Luther was dead or alive, Luther would continue the work of reforming the church until March, 1522, translating the New Testament into German, and spending time in prayer and writing. Subsequent events will be commemorated in future 500 year anniversaries.

For further reading and sources:

Roland H. Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther, Abingdon Press, Nashville, 1977

Martin Brecht, Martin Luther His Road to Reformation 1483-1521, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, 1985

James Kittelson, Luther the Reformer: The Story of the Man and His Career, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, 2003

Eric Metaxis, Martin Luther: The Man Who Rediscovered God and Changed the World, Viking, New York, 2017

Frederick Nohl, Martin Luther: Biography of a Reformer, Concordia Publishing House, St. Louis, 2003

Sacramental Union and Handling of the Elements

The Sacrament of the Altar. The Lord’s Supper. The Eucharist. The blessing of all blessings that the Lord Jesus Christ has given to His Church. Throughout our Lenten journey through the Paschal Mystery, the sermons on Sunday have been focused on this particular Sacrament. So far the posts on this blog have also been prepared in regard to a more in-depth study of the Lord’s Supper. Here are the questions we will now consider: 1) When does the sacramental union of the Body and Blood of Christ with the bread and wine of the Holy Eucharist begin? 2) How should we handle the elements used in the Sacrament?

The Sacrament of the Altar. The Lord’s Supper. The Eucharist. The blessing of all blessings that the Lord Jesus Christ has given to His Church. Throughout our Lenten journey through the Paschal Mystery, the sermons on Sunday have been focused on this particular Sacrament. So far the posts on this blog have also been prepared in regard to a more in-depth study of the Lord’s Supper. Here are the questions we will now consider: 1) When does the sacramental union of the Body and Blood of Christ with the bread and wine of the Holy Eucharist begin? 2) How should we handle the elements used in the Sacrament?

While it might seem obvious, it’s important to note that our Lutheran Confession admit only the fourfold account of the institution of the Lord’s Supper (Matthew 26:26-28; Mark 14:22-24; Luke 22:19-20; 1 Corinthians 11:23-25) as the only source for the doctrine of the sacramental union. Now, the tenses of the verbs used in each Scriptural account does not render it possible to arrive at a conclusive answer to the question of the exact moment.

Two weighty doctors of the Lutheran Church provide insightful declarations that no dogmatic answer to this question can be given. Johann Gerhard (1582-1637) writes: “[Christian simplicity] is not gravely concerned about the moments in which the Body of Christ begins or ceases to be present, but just as the mode of the presence defies research, so also it declares that these questions about the moment of the presence are unanswerable.” Johann Wilhelm Baier (1647-1695) similarly asserts: “[It is] not necessary to define the moment of time in which the Body and the Blood of Christ begin to be sacramentally united with the bread and the wine.”

Martin Luther and his supporters (ourselves as well, as we are the inheritors of the faithful doctrine of the Lord’s Supper) rightly held that the sacramental union of Christ’s Body and Blood with the bread and wine is accomplished in close temporal and causal connection with the recitation of the words of institution.

Throughout his writings, Martin Luther insisted that after the words of institution were spoken, by the power of God’s Word, the true presence of Christ’s Body and Blood had been united to the bread and wine. Particularly interesting writings include his 1520 On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, where Luther affirmed that the Body and Blood of Christ were present at the time of the elevation—when the pastor raises the host and the chalice after the words of institution. Luther’s catechism sermon on the Holy Eucharist (September 25, 1528) describes the Body of Christ as clothing itself with the bread when the Word is added to the elements.

While we cannot definitively state the exact moment that Christ’s true Body and Blood are present in the Sacrament, we do know that after the words of institution are spoken, and before the elements are placed into our mouth, Christ truly is present. Article X of the Augsburg Confession asserts that the Body and Blood of Christ are truly present in the Lord’s Supper under the form of the bread and wine and that they are distributed to and received by all the communicants. The assertion that Article X of the Augsburg Confession implies that the Body and Blood of Christ are present “in the hands of the administrant as well in the mouth of the communicant” was endorsed by the 22 LCMS participants (including C. F. W. Walther) in the second assembly of the Free Evangelical Lutheran Conference, Pittsburgh, PA, Oct. 28 to Nov. 4, 1857.

How then should we handle the elements used in the Lord’s Supper? With supreme reverence and care! For we know that the true presence of our Lord Jesus Christ is present! Here is a story that helps to shed some light on this topic. In 1542 at St. Mary’s Church in Wittenberg, Martin Luther and Johannes Bugenhagen were celebrating the Lord’s Supper with the parish. A woman communicant accidentally bumped against the chalice as she was kneeling down so that some of its contents spilled upon her clothing. Luther and Bugenhagen assisted in wiping off the woman’s jacket. After the celebration Luther had the affected portion of the lining of the jacket cut out and burned, along with the wood that he had shaved from the part of the choir stall upon which the contents of the chalice had likewise been splashed. In 1530, Luther had a host which had been placed into the mouth of a dying parishioner burned because the individual died before he could swallow.

The continual tradition of the Lutheran Church has been to display great care and reverence to the elements used in the Lord’s Supper. At St. Mary’s Lutheran Church in Wittenberg—and wherever the Lutheran Reformers taught—the preferred practice for treatment of the remaining communion elements after the last parishioner communed was to have them consumed by the pastor(s) and elders. Luther and Bugenhagen explained that to avoid having hosts left over they counted out the hosts to match the number of communicants at each service.

So here we see the great and deliberate care that is taken when handling the elements used for the Sacrament of the Altar. We are careful and reverent because the true Body and Blood of Jesus Christ is present with the bread and the wine. People loved by God, when you come to altar and receive the host and the wine…you hold Jesus in your hands! There He is! Exactly where He has promised to be. And He delights to come to you in such a way to deliver to You forgiveness, unity with Him, His divine grace, and the promise of eternal life. You hold in your hands the most sacred and precious thing in all of the world! And you get to place that treasure of infinite worth into your own mouth!

In summary: As Lutherans we cannot assert less than that the true Body and Blood of Christ are truly and essentially present in the Eucharist and that with the consecrated bread and wine they are distributed to and received by all who use the Sacrament.

Any attempt at defining the precise moment at which the sacramental union begins—at consecration, at the beginning of distribution, or any point in between—must remain in the realm of theological opinion.

Finally, we must be sure to also handle the communion elements with the utmost care and reverence. Rejoicing in the great gift that our Lord Jesus Christ Himself delivers to us. May we all look forward to receiving this blessing of all blessings again soon!

The Lord’s Supper During A Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic that shut down Michigan in March, 2020, changed and challenged many church practices that most of us took for granted. One of the most significant impacts was on the celebration of the Lord’s Supper. Christians have been celebrating the Lord’s Supper for 2,000 years, through plagues, pandemics, wars, and all sorts of calamities, so this is not a new challenge for Christians. It is new, however, to our generation, which has not had so many hurdles set up to receiving the Lord’s Supper in our lifetime. A greater understanding of health and cleanliness also makes our generation distinct in the ways we are challenged by the restrictions of pandemic ministry.

The COVID-19 pandemic that shut down Michigan in March, 2020, changed and challenged many church practices that most of us took for granted. One of the most significant impacts was on the celebration of the Lord’s Supper. Christians have been celebrating the Lord’s Supper for 2,000 years, through plagues, pandemics, wars, and all sorts of calamities, so this is not a new challenge for Christians. It is new, however, to our generation, which has not had so many hurdles set up to receiving the Lord’s Supper in our lifetime. A greater understanding of health and cleanliness also makes our generation distinct in the ways we are challenged by the restrictions of pandemic ministry.

The Lord’s Supper was instituted by Jesus Christ himself, when He celebrated it with His disciples and told them to “Do this in remembrance of me.” (Luke 22:19) We receive in the bread and wine the very body and blood of Christ, given and shed for us for the forgiveness of our sins and strengthening of faith, as well as the pledge of a resurrection life. The Lord’s Supper is something believers crave and hunger for, as it unites us with Jesus and each other. But what happens when a pandemic disrupts our regular reception of the sacrament?

During the stay-at-home orders, many Christians “fasted” from the Lord’s Supper, as did our congregation when we had only livestream services from March through June. Others have been worshipping online this entire year, due to health risks or other concerns. They plan to take the Lord’s Supper again once they have been fully vaccinated. Some have been in nursing homes or facilities where visitors have not been allowed. This past year, many Christians have gone the longest without the Lord’s Supper than ever before since their First Communion.

The book, Faith in the Shadow of a Pandemic (Corzine & Pless, CPH, 2020) treats the topic of the Lord’s Supper in an entire chapter. In it, they recall from the Scriptures and the Lutheran Confessions that we celebrate the Lord’s Supper from Christ’s institution, and are discouraged from “making stuff up” when it comes to the sacrament. This had already happened in extreme ways during the Middle Ages, when medieval Christianity had a number of innovations regarding the sacrament. They had private masses, reservation of the host, Corpus Christi processions, and reserved the wine for the priests only. These and other inventions were discarded by the Lutheran Reformation, which focused on the words given in Scripture.

The book, Faith in the Shadow of a Pandemic (Corzine & Pless, CPH, 2020) treats the topic of the Lord’s Supper in an entire chapter. In it, they recall from the Scriptures and the Lutheran Confessions that we celebrate the Lord’s Supper from Christ’s institution, and are discouraged from “making stuff up” when it comes to the sacrament. This had already happened in extreme ways during the Middle Ages, when medieval Christianity had a number of innovations regarding the sacrament. They had private masses, reservation of the host, Corpus Christi processions, and reserved the wine for the priests only. These and other inventions were discarded by the Lutheran Reformation, which focused on the words given in Scripture.

In the Smalcald Articles, one of the confessional writings, it states, “If some want to justify their position by saying that they want to commune themselves for the sake of their own devotion, they cannot be taken seriously. For if they seriously desire to commune, then they do so with certainty and in the best way by using the sacrament administered according to Christ’s institution. On the contrary, to commune oneself is a human notion, uncertain, unnecessary, and even forbidden. Such people also do not know what they are doing, because they are following a false human notion and innovation without the sanction of God’s Word. This it is not right (even if everything else were otherwise in order) to use the common sacrament of the church for one’s own devotional life and to play with it according to one’s own pleasure apart from God’s Word and outside the church community.” (SA II II 8-9, Kolb Wengert p. 302-303)

In so many areas of ministry, we have had to be innovative, creative, and flexible to bring God’s Word and fulfill the mission of the church. These, no doubt, have been used by the Spirit for fruitful ministry. However, in the area of the Lord’s Supper, we are much more cautious about making too many changes that would undermine the basic elements of consecration and distribution. Yet even in this, not all churches will be identical in this regard. We try to demonstrate charity and grace to fellow Lutherans who may have decided to make more significant alterations to their consecration and distribution of the Lord’s Supper. All of us were trying our best to adapt to the situation. However, as we move forward, thoughtful reflection and theological discussions will need to be had with a spirit of humility and trust as we seek a faithful way forward.

Celebrating the Lord’s Supper at Our Savior Lutheran Church and School, Lansing, MI

Holy Communion at Our Savior is offered to members of our congregation and to those who have been instructed in the beliefs and practices of our congregation and the Lutheran Church regarding the Sacrament. The practices of our congregation flow from our beliefs regarding what is happening in the celebration of the Lord’s Supper.

According to the Center for Disease Control at that time, touch was not a likely method for transmitting COVID-19. Transmission happens mainly through respiratory droplets breathed into the air, and mucous or saliva droplets spread through sneezing or touching one’s mouth, eyes, nose, etc. This made us focus on the three W’s that were consistent with the health measures that our school ministry had put in place – Wash your hands, Watch your distance, Wear your mask.

All Elders (and all communicants – everyone in worship actually) wash their hands thoroughly before worship and distributing the sacrament. Prior to distribution, pastors and elders use hand sanitizer to ensure our hands are clean before handling the wafers / host and the cups of wine. Masks are worn at all times by those distributing. Those communing may briefly remove their mask to receive the Sacrament. The brief time when communicants remove their mask to receive the sacrament is not a risk factor. We are confident that receiving Holy Communion with these health practices in place is not a source of transmission for COVID-19. The benefits of the Sacrament far outweigh any minute risk from being in person for worship or taking the Lord’s Supper.

The Common Cup is a concern in many people’s minds, and yet in the past it has not really been a source of transmission for colds or the flu. The alcohol in the wine reacting with the precious metals has long thought to mitigate germ transmission. The risk of catching something is very low, especially compared to the high transmission activities like shaking hands. However, since the invention of little individual cups, many people prefer that to the common cup because only the altar guild and pastor distributing touch the cups. The altar guild and the pastor/vicar use rigorous hand washing to ensure that their hands are clean. We are using the common cup only for consecration, and only the individual cups for distribution.

When approaching for Holy Communion, there are hash marks on the carpet of the center aisle. This is so households can keep 6 ft distance from each other while in line to come forward. They may stay together as a family/household while communing at each station.

When approaching the elder to receive the body of Christ, the communicant may remove their mask and lay their palm flat. The elder places the host into their hands and they then place it in their mouth.

When they move over to the wine station, the pastor/vicar sets out the number of individual cups of wine for that family and then steps back. They take the cups and drink the wine as the pastor speaks the words of distribution. There is a cup of white de-alcoholized wine on the tables for those who desire it. After receiving the blood of Christ, they put the empty cups in the baskets as you return to their seats.

We are confident that the distribution of the Lord’s Supper poses extremely low risk for transmission for COVID-19, and that we can receive the Sacrament joyfully, confidently, and in the fellowship of believers as Jesus gives us forgiveness, life, and salvation.

Questions that still remain for the future practice of the Lord’s Supper are: 1) When will we use the rails to kneel for the Lord’s Supper? 2) When will we fill the baptismal font for people to touch on their way to the rail? 3) When will we use the common cup again? These are in addition to the questions about how long we will require masks, distancing, and hand washing and all the other mitigation efforts that have become the new normal. We pray for the Spirit’s continued wisdom and guidance as we move forward in faith, hope, and love.

In addition to in-person worship service and the celebration of the Lord’s Supper as described above, our church staff also brings communion to people’s homes upon request, and to our shut-ins on a monthly basis. A special parking lot service on April 18 will provide yet another opportunity for people to receive the Lord’s Supper if they are not ready to participate at in-person services.

The disruption of these long-held practices forces us to revisit our beliefs and convictions about the Lord’s Supper and Jesus’ intention and institution of it. This can very well lead to a deeper appreciation for the Sacrament, and a renewed understanding of its place in the Christian life. That is the reason for our Sunday morning preaching series in Lent 2021 on various facets of the Lord’s Supper, and the ongoing invitation to gather at the table of the Lord. We pray that the Lord will continue to strengthen and bless our church as He feeds and sustains us, so that we may continue to be the body of Christ in the world.

Benefits of the Lord’s Supper

Greetings, people loved by God!

Welcome to the beginning of the Our Savior Lutheran blog. Pastor Wangelin and I (Vicar Heinze) will be using this blogsite first for a group of posts about the Lord’s Supper. These posts will be coming out along with our sermon series: Hungry Hearts, for Lent 2021.

Before we can dig into many of the topics we will be discussing in regard to the Lord’s Supper, it’s important for us to have a solid foundation of what the Lord’s Supper is and what the benefits of the Sacrament.

The Lord’s Supper goes by many names, both in Scripture and by the Church: The Lord’s Supper, the Sacrament of the Altar, the Eucharist, the breaking of the bread, etc. I have often heard the Sacrament of the Altar referred to as an “it” or “thing.” But it is much more a “Who.” In the Sacrament, we encounter Christ Himself. This is how the Small Catechism says the head of the home should teach the family about this great reality in a simple way:

What is the Sacrament of the Altar?

It is the true body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ under the bread and wine, instituted by Christ Himself for us Christians to eat and to drink.

Where is this written?

In the same way also He took the cup after supper, and when He had given thanks, He gave it to them, saying, “Drink of it, all of you; this cup is the new testament in My blood, which is shed for you for the forgiveness of sins. This do, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of Me.”

As we read these words, we discover how simple they are; yet they are also very profound. Through these words, Jesus Christ Himself tells us exactly what He gives to us in the Sacrament and exactly why He gives it. Luther’s Small Catechism calls what He gives us “the true body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ,” and the word “true” here is essential for any discussion on the Lord’s Supper. That words eliminates any attempt or ability to worm out of what Jesus actually says: “Take, eat; this is My body, which is given for you” and “Drink of it, all of you; this cup is the new testament in My blood, which is shed for you for the forgiveness of sin.” He tells us it is His body, and it is the body given for us. Think about that! The same body and blood that was born of the Blessed Virgin Mary! The same body that was crucified and nailed to the cross! The same blood that stained the wood, that poured from His wounds, that wiped out the sin of the world!

One of the most well-known Scripture accounts is Jesus’ teaching to become like little children, for they are known for believing what they are told. And when we come to the discussion of the Lord’s Supper, guess what…it’s time for each of us to become like little children again. In the Sacrament we are presented with an unfathomable mystery by Jesus Himself, yet an overwhelmingly delightful mystery. In the Lord’s Supper, it is Jesus Himself who takes His own body and blood that was used to win our salvation and gives them to us to deliver that salvation into us. Jesus holds it out to us, as the catechism says, “under the bread and wine” and tells us to eat and drink it.

Lord Jesus Christ, we humbly pray

That we may feast on You today;

Beneath these forms of bread and wine

Give us, who share this wondrous food,

Your body broken and Your blood,

The grateful peace of sins forgiven,

By faith Your Word has made us bold

To seize the gift of love retold;

All that You are we here receive,

And all we are to You we give.

— LSB 623:1-3

Do you see that as you read these words? Do you hear it as you sing them? Look and see how we confess that when we go to receive the Lord’s Supper, we do not receive an “it” but a “Him’! This hymn clearly states our confession that in the Sacrament we actually feast on Christ, His body and blood beneath bread and wine!

But why did Christ give us this gift and command us to “do it” “often” “in remembrance of” Him? The Small Catechism turns to that next:

What is the benefit of this eating and drinking?

These words, “Given and shed for you for the forgiveness of sins,” show us that in the Sacrament forgiveness of sins, life, and salvation are given us through these words. “For where there is forgiveness of sins, there is also life and salvation.”

Jesus’ words here, “Given and shed for you for the forgiveness of sins,” proclaim the foundational reason why He gives His body and blood to us in the Sacrament. We must make note that sometimes Christians have been confused in regard to an important distinction: the difference between how salvation was won and how salvation is bestowed. Obviously, there is absolutely no question that the salvation of the world was accomplished by Jesus Christ as He sacrificed Himself once-and-for-all on the cross.

However, if the salvation of the world was accomplished by Jesus on the cross two-thousand years ago, how is that salvation accessible to us now in the present day? Some of our Protestant friends like to sing a hymn that says: “There is power, power, wonder-working power in the blood of the Lamb.” We’d agree. There is! But we’d also ask: “And where can I find that blood?” In the Lord’s Supper, at His Altar, the Crucified and Risen Savior gives the salvation that He won by His once-for-all sacrifice on the cross.

Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross was offered only one time; however, in the Lord’s Supper, our same Living Lord comes to us every time with the very body and blood that were the ransom price of our bodies and souls; through them, He gives us His forgiveness. And, “where there is forgiveness of sins, there is also life and salvation.” Where the Son of God comes to you in love, gives you forgiveness, and pours into you His divine life, there you also discover salvation. Salvation is communion with the Father through the Holy Spirit.